Drugs. Alcohol. Vaping. Whatever you want to call it, substance abuse in Judge Memorial and many other high schools has been prevalent for a long time.

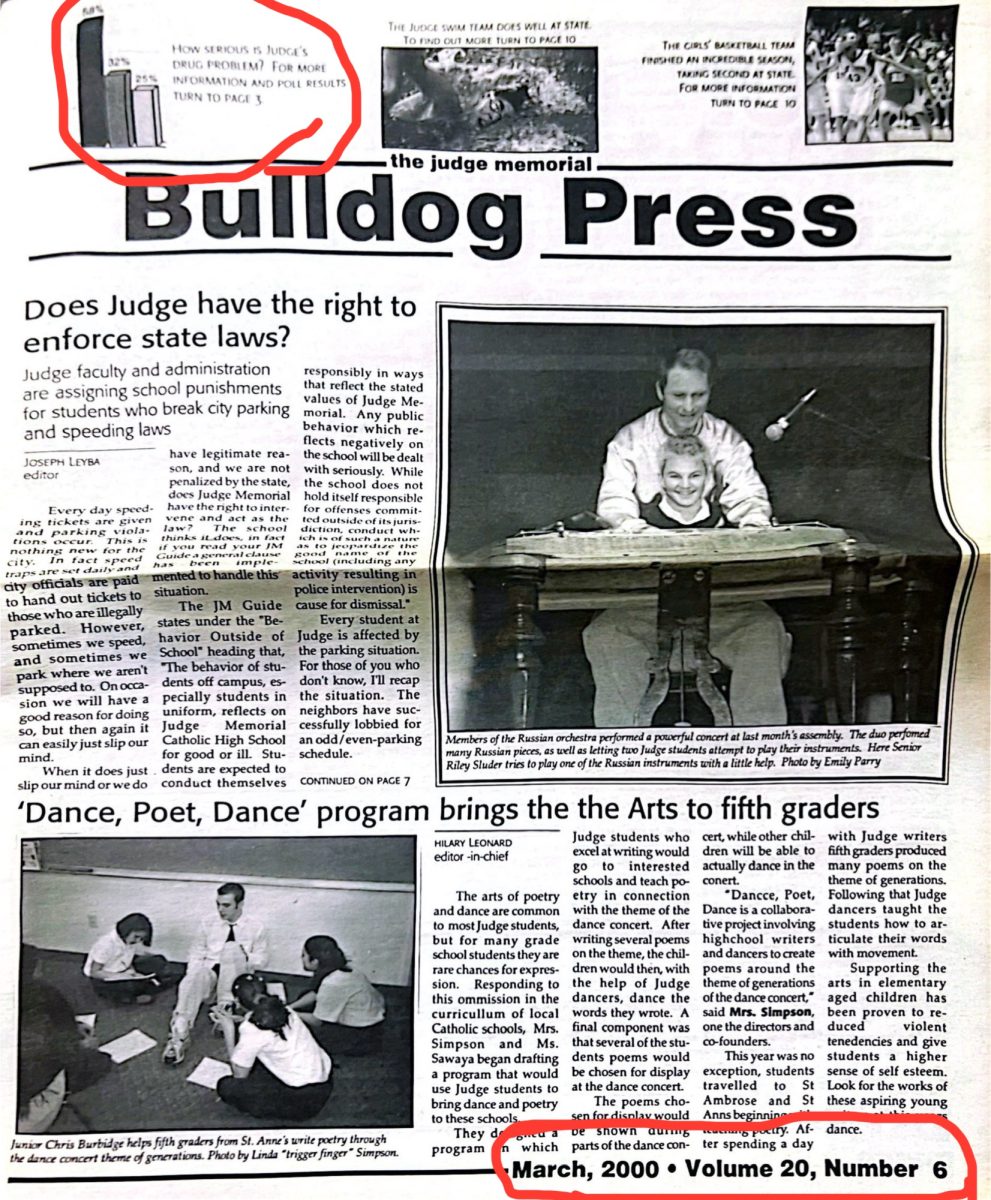

This year marks 25 years since a poll by the Press on Judge students was conducted on substance abuse. The poll asked 114 randomly selected students, “Have you ever used [drug/illicit substance] in the past [time period (thirty days, year, lifetime)]?” According to staff writer Mat Pardini, the results were eye opening. Fifty-five percent of the student body had consumed alcohol in the past 30 days alone, and 32% had done some form of marijuana. Thirty-seven percent had smoked cigarettes.

Today, accurate information on substance abuse is difficult to obtain. It is hard for student-run organizations like the the Press to obtain honest responses with the student body for a variety of reasons, such as trust and staff levels. Rightly so, many students would balk at responding to a poll given to students 25 years ago with the same name and same questions unless they know who they’re giving that information to and that it can’t be traced back to them. And because of this, we can’t accurately say what percentage of Judge students currently use illicit substances.

However, what we can look at is the student perception of why their peers leave Judge. When an individual is suddenly absent from the student body, the first student explanation points to Judge’s drug testing policy. This is an example of how frequent experiences like these reflect a broader potential problem within the student body, and perhaps warrants a review of Judge Memorial’s policy on substance abuse amongst the study body and their efforts to control it.

What is Judge’s policy on illicit substances? There’s a summary from the Student Handbook that can be found in the planner given to every student at the beginning of the school year and online at judgememorial.org.

To summarize, there are two ways in which students can be tested. Either they are suspected of abuse, or they participate in student leadership activities. The student is then taken out of class. It’s not clear whether this is with or without prior knowledge; however, there are rumors that some people fake their tests, or that they are contacted with a date in advance. The student is taken to one of two locations: the football locker room or the “back room” behind the counter where the announcements are done and the assistant to the dean has his office. The student is given the choice of a hair follicle test or a urine test.

Once the test is collected, it heads to a separate facility to be tested. In one to three weeks, results come in. If positive, students go about their lives. If negative, however, a follow up test will be required, along with different wellness initiative practices such as seeing a licensed therapist. The school pretty much has free reign over what it wants to do with students who fail tests, beyond having the ability to dismiss anyone from the school at any time.

One thing missing from the handbook is why drugs are detrimental to one’s health.

Societally, it’s easy to understand the reasons that drug use can severely impair someone’s health. Despite this general knowledge, drugs are clearly still used.

Instead of taking the issues of illicit substances as given knowledge, the handbook should be updated to reflect why substance use and abuse are specifically bad for your health. For instance, it should be stated that smoking can cause lung cancer and a litany of other cardiovascular problems later in life. Marijuana overuse can spur anxiety and depression through addiction. Alcohol use in teenagers has been shown to negatively impact brain development, and long term rates of alcoholism are significantly more likely the earlier someone starts drinking. In addition, the longer you delay drinking, the less likely you are to have problems associated with addiction, mental health, and physical health, including death. These specific examples could be included in the handbook to potentially educate students and families on why substance abuse must be addressed on an individual level.

Speaking of addressing the problem, the question of how substance abuse should be handled gives us three options: societally, individually, or a mix of both. Currently, it seems like the school is using a largely individual (and as autocorrect wanted me to say, seemingly “ineffective”) option. As stated above, students are enrolled in a random drug testing program. We don’t know how long this program has been running. However, the 1999 article about the substance abuse survey seems to allude to its potential introduction.

A possible positive effect towards solving the problem societally is the teaching of the state mandated Health class to freshmen, in which a unit covering the health effects of substance abuse is taught. While a good start, this is nowhere near enough to keep students from having substance abuse issues. The unit in question can’t be longer than a month, or 17.5 classroom hours, of school.

While benefiting students in the short run, this program could be expanded throughout the four years at Judge.

Each year, students could be reminded of potential harms, ways to avoid, and resources for help in avoiding or stopping using throughout the high school student’s tenure. We should be actively talking about this problem and treating it like a real societal crisis, not overloading students in their first year of high school and then forgetting it the rest of the way.

However, none of this will come to fruition unless the Judge community addresses the problem. It is likely that other schools have similar, if not the same substance abuse problems in their student bodies. I bet they might be worse quite simply because Judge’s testing could work as a partial deterrent. This is one area Judge has excelled at in doing something rather than nothing. But it must go further.

A solution that our school could spearhead is an open initiative acknowledging substance abuse in the community. This would pave the way towards putting forth a real, tangible plan that really works. Ultimately, it could truly keep kids away from these problems.

And yes, coming out and admitting that Judge has a drug problem might cause issues with the school. Parents may decide to send their kids elsewhere, leading to bad societal representation and financial struggles for the school. However, are we not supposed to be builders of a more just society? What are we if we bow to the very people that demean my fellow classmates for problems that those very same people either pretend aren’t real or don’t do anything meaningful to solve?

In the long run, Judge only serves to benefit from making its drawbacks public. In admitting substance abuse is a real, tangible issue along with why it’s so terrible, then we can start to create solutions together to tackle the problem as a whole. Ultimately, we would be the golden example in our community of victory against substance abuse. We’d be able to truly look back at our work with pride, and look forward towards a more perfect future.

For now, however, if you’d like free, confidential help with substance abuse issues, you can call SAMHSA’s national hotline at 1-800-622-4357.